The Great Repricing (that should be happening?)

Everyone agrees that private “growth” assets aren’t worth what they were valued at for their last round, but few stakeholders, from the companies themselves to LPs want to admit it. Why is that?

The WSJ reports that Tiger Global marked down the value of its VC investments by roughly 33% in 2023 - a $23 billion reduction in the value of its startup holdings. Schroders cut the valuation of its Revolut stake by 46%, writes the Irish Times. Allianz puts its N26 stake up for sale at a discount of 68% according to the FT.

How GPs should mark their private investments remains a controversial problem. For public portfolios, value is “marked to market” every day, using the closing prices for the held shares. For private companies, the general rule is to use the last fundraising price, if it happened in the last 12 months. If the last round is over a year old, GPs are expected to reassess the fair value of their stake - typically with an independent valuer.

Growth funding in Europe was down over 70% year-on-year in Q1 2023. Virtually none of the companies that raised in 2020 or 2021 returned to the markets in 2022. This means that for most of the value drivers in European venture portfolios, we are now well past the 12-month mark. Yet, most limited partners (LPs) report that their GPs have left the majority of their marks unchanged (or only very marginally so).

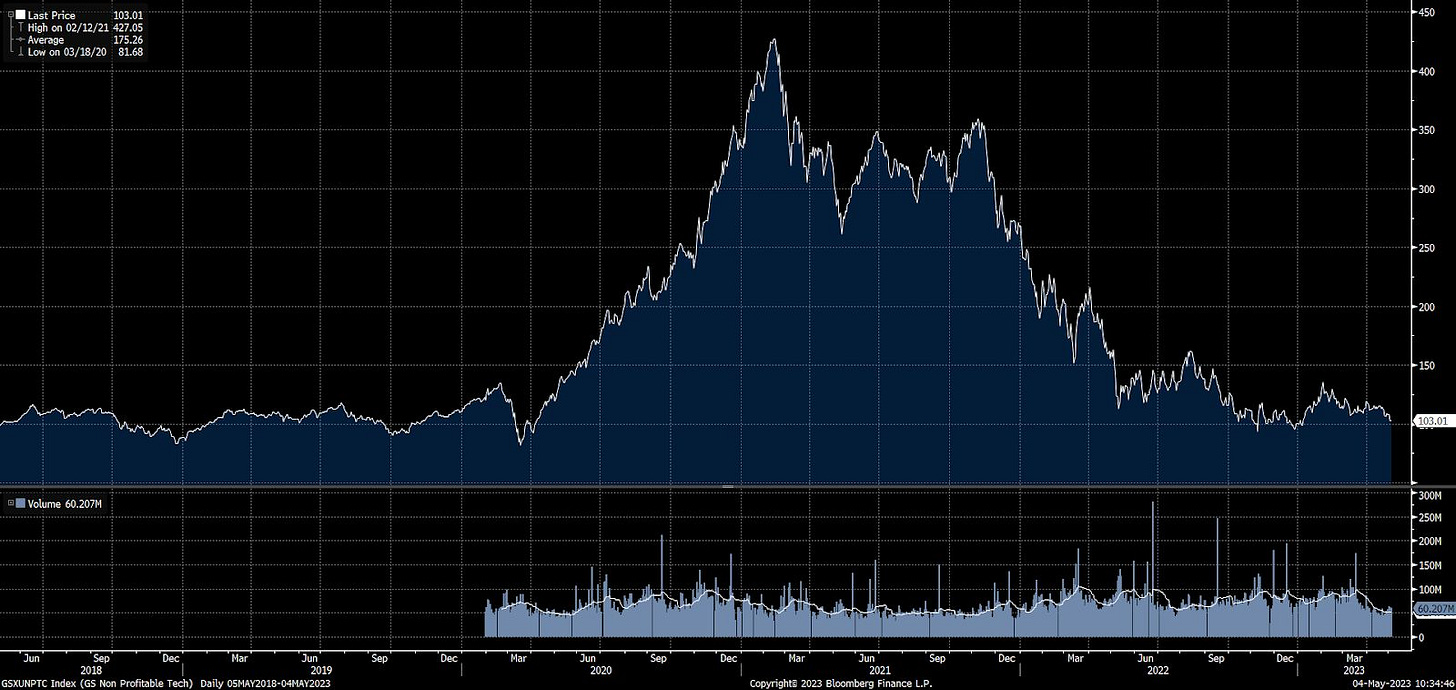

The unmoved marks have surprised some LPs, given unprofitable publicly-traded companies have seen their valuations dwindle (see Goldman’s “Unprofitable Tech” index below). In some cases, this can lead to absurd situations. One LP mentioned there was a company to which they had exposure through three different funds, who were holding the asset at 3 different prices… with the highest valuing it at three times the price of the lowest.

The topic has attracted some commentary - Clifford Asness, the founder of hedge fund AQR, coined the term “volatility laundering” to describe private equity fund managers who understate the fluctuations in the value of their portfolios.

The issue in part seems to be a typical principal-agent problem:

GPs would rather keep the higher marks to help with raising their next fund.

LPs who usually have significant public equities exposure benefit from private equity valuations remaining stable, in order to mitigate (in appearance) the overall impact on their portfolio.

Companies, who would rather avoid the bad press (and internal challenges) that come with accepting a downround.

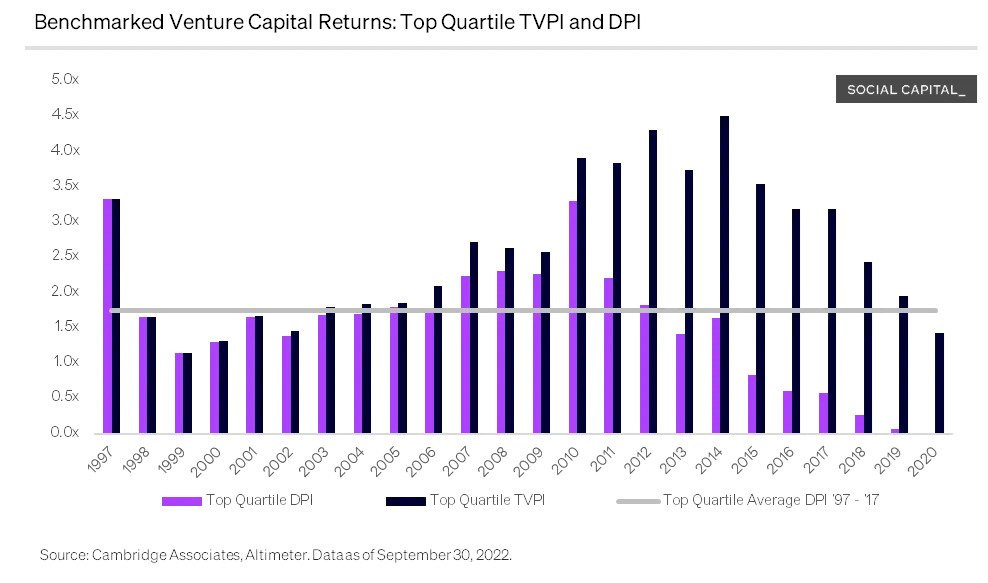

So far, it seems that a lot of the “TVPI” (the accounting value of the portfolio) will not transform into “DPI” (actual cash on cash returns), leaving the people whose capital is being managed worse off than they may have thought and creating more and more pressure on funds to facilitate transactions for returns to materialise.

This actually leaves everyone worse off, trapped in a classic prisoners’ dilemma where no one has an incentive to make the move that would improve everyone’s outcomes:

LPs consider themselves “overallocated” to venture & growth - this means they are less likely to commit to new funds and miss out on interesting vintages

GPs find it more difficult to fundraise overall, because LPs have to adjust to the “denominator effect” - because the accounting value of venture & growth assets has decreased less than the rest

Unrealistic expectations can dampen companies’ chances of raising more capital, and might even lead to a mass extinction event of startups (read also Elad Gil’s post on the great reckoning)

Why does this repricing matter for direct secondaries in venture and growth?

Some of the best companies raised years of runway in the ‘20-’21 boom years and this means that secondaries will be the only way to invest in them until they return to the market. A meaningful proportion of secondary activity is driven by investors who are not the most active primary investors: family offices, funds of funds, hedge funds etc. Typically, they rely on the valuation work done by VC and growth equity firms to anchor their entry price. Now though, those investors know the last round valuations are wrong, but aren’t sure how wrong.

This unstable equilibrium is being challenged from two angles. On the one hand, most investors expect a large contingent of companies to return to the market in the second half of 2023 and first half of 2024, as their runway extending efforts hit their limit. Many expect this crowding effect will lead to lower valuations for those companies who get funded. Reviewing valuations will also be important to continue incentivising talent properly, as Stripe had done multiple times before their most recent (down) round.

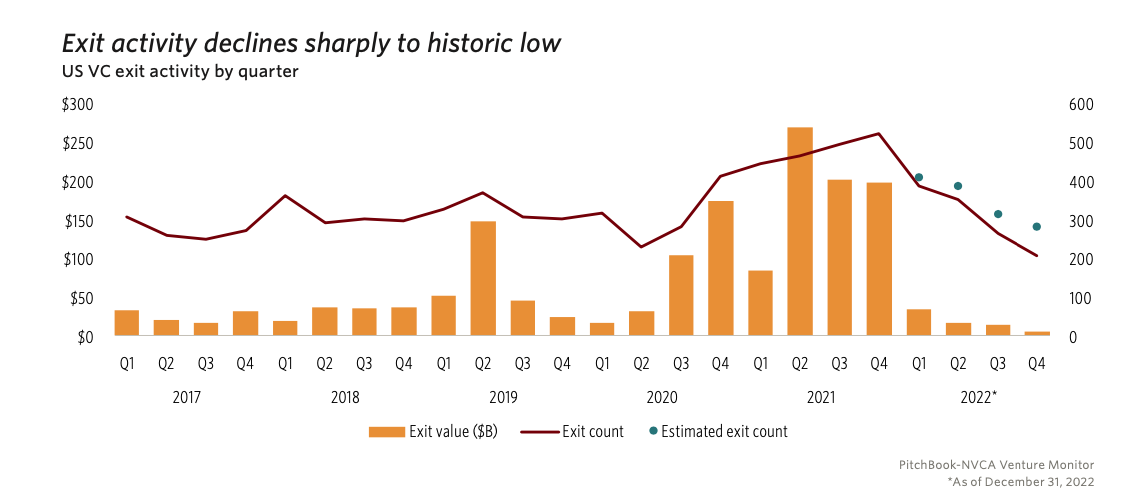

On the other hand, with an extended drought of exits, sellers with diverse motivations (employees for personal finance, LPs/GP for portfolio rebalancing or to get actual cash returns..), after hoping for a V-shaped recovery, are coming to terms with the fact their equity may not be worth what it was 18 months ago. This increased supply of shares for sale will also create downwards pricing pressure.

We expect these dynamics to accelerate the overall repricing of growth assets and to significantly increase the volume of direct secondaries, after a rather calm 12 months. This will allow these fast-growing, iconic companies to welcome new, long-term backers to their cap tables. The best among these companies continue to compound value - and the market is now pricing in line with that value. As is always the case, some investors will be ahead of the curve and rewarded for being greedy whilst others were fearful.

Semper does not provide investment advice. Semper Unitas Limited is an Appointed Representative (Firm Reference Number: 963550) of Khepri Advisers Limited (Firm Reference Number 692447) which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.